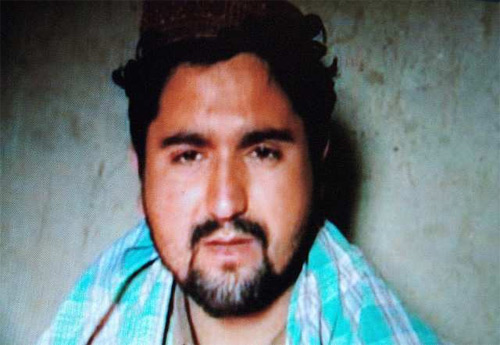

The death of Ajmal Naqshbandi

Ever since his videotaped beheading by the Taliban on the afternoon of Sunday, April 8, Ajmal Naqshbandi has become a household name in Afghanistan. No death in recent years has so galvanized public opinion here. Like the murder of Margaret Hassan in Iraq a few years ago, Ajmal’s has come to epitomize the horror of the war in Afghanistan.

His beheading was the culmination of a harrowing month in captivity for Ajmal, a 24-year old journalist from Kabul. He was taken hostage in Helmand province on March 4, together with La Repubblica reporter Daniele Mastrogiacomo, and their driver Sayed Agha. They had travelled there for a rendezvous with the Taliban; Ajmal was working as the Italian’s fixer, as he had done for other foreign reporters in the past.

But the meeting that had been arranged for them was a trap. Instead of granting Mastrogiacomo an interview, the Taliban took him and his companions hostage, and proceeded to use them as expendable pawns in a horrifying game of death. Sayed Agha, the young driver, was the first to die. He was beheaded by the Taliban shortly after the group was abducted. The Taliban posted a video on the internet showing the three blindfolded men seated on the ground at the feet of their captors.

Then one of the Taliban spoke to the camera, condemning Sayed Agha to death for being a spy. He then slit Sayed Agha’s throat, and cut off his head. A weeping Mastrogiacomo was shown pleading for his life and begging for his captors’ demands to be met. And they were. A few days later, on March 19, the Italian was freed in exchange for five senior Taliban prisoners held by the Afghan government.

Afterwards, President Hamid Karzai haplessly explained that he was pressured by the Italian government – which has 1,800 troops in Afghanistan – to make the exchange. After Mastrogiacomo’s release, however, Ajmal remained in Taliban hands. Supposedly, he was being held until the government handed over two more Taliban prisoners.

But then, two days before the expiration date they executed him. Government officials gave unconvincing explanations as to what had gone wrong, but the damage was done. To Afghans, it appeared that their own government cared more about an Italian than one of its own citizens.

There are several theories floating around as to why Ajmal was really killed, but, whatever the truth, it was a watershed event in Afghanistan. On the one hand, it was a sign that the Taliban were prepared to take their terror tactics to a new level, and that the Afghan government was weak and indecisive. Most importantly, for journalists, it meant that henceforth, similar rendezvous with Taliban fighters in the field might be fatal.

It also means that the handful of savvy, experienced and reliable "fixers" like Ajmal no longer want to risk death by arranging such meetings for foreign reporters.The bottom line: Since the Taliban got what they wanted by kidnapping Mastrogiacomo, it now means that all Westerners, including journalists, have become potentially valuable commodities in the Afghan war – just as they have become in Iraq.

Understandably, the episode has raised the tension levels in Afghanistan to a new high, and raises serious questions about how journalists can accurately report the war here. The killing of Ajmal, above all, highlights the vital and sensitive role local fixers play for all of us who report here and elsewhere. It raises the question of what our responsibility is towards such people when they are victimized for assisting us.

Most reporters who come to Afghanistan do not speak Dari or Pashto, the country’s principal languages, and do not possess the contacts to move around and report unassisted. Whether our published stories reflect it or not, most of us are dependent on fixers, translators, and drivers here in order to do our work -people like Sayed Agha and Ajmal Naqshbandi.

A couple of weeks ago, I visited Ajmal’s family in Kabul and his father told me that, so far, he’d received no offer of help or compensation from either the Afghan or the Italian governments.He is a former aviation mechanic for Ariana airlines, but lost his job after losing a leg in a land mine explosion back in the Nineties.

He was very proud of Ajmal and the work he had been doing, he told me. He pointed to his two surviving sons, both teenagers, who were sitting in the room with us. He said: "Ajmal was the sole breadwinner of our family; he wanted them to go to college. Now I don’t know what we are gong to do for them."

Ajmal’s father wasn’t insinuating anything, he didn’t have his hand out, he was merely stating the facts, and he uttered his words with great dignity. After a time, I got up to leave. He thanked me for coming and I said goodbye, leaving him to his grief. His two sons saw me to the door and smiled and waved as I left.

In the past several weeks, journalists in New York and London have been trying to raise funds for Ajmal’s and Sayed’s families. Hopefully they will raise enough to show both families that we – all of us – really do care about them.

It will not only provide real help to their families; it will also send proof of our compassion throughout Afghan society. We could go even further. There can be no better moment than this one to establish a special compensation fund for the indispensable, underpaid and often unnamed Ajmals and Sayeds who pull us through and help us get our stories around the world, and who, increasingly, are paying the ultimate price for doing so. It could be called The Ajmal Fund.

Frontline Fixers Fund

In response to the murder of Ajmal Naqshbandi in Afghanistan we have started a fund for the families of fixers killed or injured while working with the international media. 100% of the money collected will go to Ajmal’s family. Please donate here