Nagorno Karabakh: Blogs, social networking sites cross ethnic fault lines

In May, Armenia and Azerbaijan will mark the 15th anniversary of the 1994 ceasefire agreement which put the conflict over the disputed territory of Nagorno Karabakh, a mainly ethnic Armenian-populated autonomous oblast situated within Azerbaijan, on hold. Since then, international mediators continue to talk of a lasting peace agreement being in reach, but few following the negotiations are as optimistic.

With a new generation of Armenians and Azeris growing up unable to remember the time when both lived together, it’s perhaps no wonder. Nationalists and politicians in both countries continue to exploit the unresolved conflict to further their own political and economic ambitions — and despite the overlaps in culture and history which Thomas de Waal, author of Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War, touched upon during an interview in 2002.

Yet, civil society groups appear to half-heartedly engage in peace-building initiatives, apparently only in order to receive funding from international donors, and change their position depending on local political developments. However, there could be a glimmer of hope if a recent documentary aired on Al Jazeera English is anything to go by. Visiting the Caucasus late last year, journalist Michael Andersen discovered such an example in the Republic of Georgia.

While fixing the Armenia leg of the film, Michael told me about a Georgian village where Armenians and Azeris live, work and study alongside each other. Footage of the school in Sopi is now available online as part of the second half of the 22-minute documentary. Brief it may be, but the sight of teachers and children from both sides working and studying together is encouraging.

Although the two ethnic groups follow different religions, for example, one Azeri child seems hard pressed to name any differences other than language.

In Baku, an alternative voice among the local media went further.

Nowhere in the world can you find two groups of people closer to each other. That is why we often have these stupid disputes between Armenians and Azeris. "This house is Armenian" or "this house is Azeri." Or "this music is Armenian or Azeri." This is exactly because the two have so much in common. […] I normally say, and people don’t like this, that Armenians are just Christian Azeris and Azeris are just Muslim Armenians. That is how much they are alike. […] link

But perhaps that isn’t so surprising.

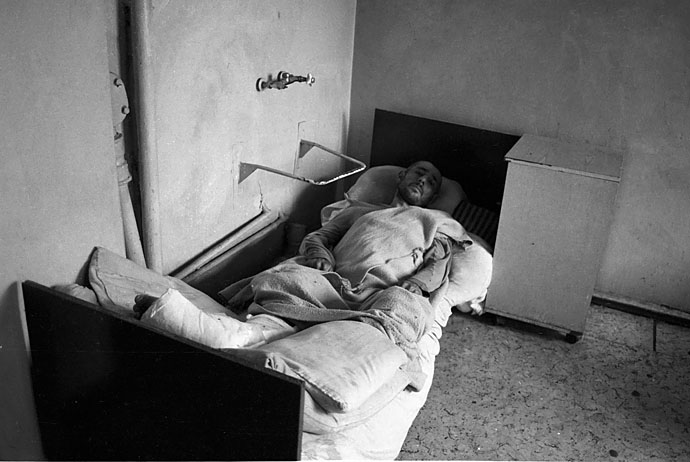

On my first visit to Nagorno Karabakh in 1994 for The Independent, I photographed prisoners of war held in the self-declared republic’s capital, Stepanakert, and remember the Armenian children playing with the kids of Azeri civilians also held hostage. Others would add that not only do both live side by side in Moscow, but in order to reach Tbilisi from Yerevan, Armenians have to pass through the mainly Azeri-populated Georgian region of Marneuli.

They do so without encountering any problems, but the situation in Armenia and Azerbaijan is very different.

Media outlets, civil society groups and political parties alike continue to push propaganda intended only to perpetuate hatred rather than resolve a conflict which arguably holds back the democratic development of both countries and also threatens the long term stability of the South Caucasus. Thankfully, a recent conference in Vienna organized by International Alert finally recognized the problem although the resulting conclusion was long overdue.

Participants in the forum discussed the possibility of holding mutual visits on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border, as well as online discussions and lectures. Details on such initiatives remain in the works. A final document, adopted without the co-chairmen’s participation, agreed with the Minsk Group that "civil society . . . is insufficiently informed and is misinformed." It added that "language of enmity is used increasingly." link

Certainly, the Internet changes the entire situation. Moreover, it had been doing so long before the conference participants owned up to their own failings, as the American University’s Center for Social Media wrote in November.

Bloggers in the South Caucasus are multiplying overnight. As Internet access becomes more common and the first post-Soviet generation grow older, blogs in this region flourish. […] […] […] With blogging becoming such a popular tool for self-expression, it will be interesting to see if the ripe moment emerges when Georgians, Azerbaijanis and Armenians really do have a reason to unite together. It is my guess the blogosphere will be the place in which it happens. link

Having already met Azeri bloggers in Tbilisi, I’ve also made contact with other bloggers from Azerbaijan online even if I still can’t visit the country on a British passport. At the same time, Facebook and Internet chat has transformed these initial contacts into normal online social interaction. The possibilities are endless, and a new project launched in January hopes to build on that in order to bring Armenian, Azeri and American teenagers together.

As mentioned in a previous post on this blog, DOTCOM has literally harnessed the power of the Internet to circumvent ethnic fault lines. Yes, there are still obstacles that need to be overcome, but the potential for the project funded by the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs and implemented by Project Harmony is there. Already, participants are showing that the issues which concern them most are common to all.

So, when DOTCOM asked whether I would agree to be interviewed along with an Azeri analyst/blogger as a project module

for the 90 participants to respond to over the next rwo weeks, I jumped at the chance.

After reading our DOTCOM interview with our two professional bloggers Arzu Geybullayeva and Onnik Krikorian, below, please ask one question (right here in the COMMENTS box) about media, blogging, social change, and citizen action here – and feel free to add to the conversation as it unfolds. link

Of course, it remains to be seen how the online conversation will unfold, but it can only be hoped that DOTCOM and other similar initiatives will achieve results. Fifteen years ago I met my first Azeris held captive in Nagorno Karabakh, but now I am meeting professionals and friends online or in Tbilisi. The Internet keeps lines of communication open even if there are those in both countries who would rather they didn’t exist at all.

Only last week, for example, I spoke to an Azeri friend in Baku over Skype. With telephone communication to Armenia reportedly blocked, it was the first time she had ever spoken to an "Armenian."

Photo: Azerbaijani Prisoner of War, Stepanakert, Nagorno Karabakh © Onnik Krikorian / Oneworld Multimedia 1994