Incredible India by David Rieff

The term “Asian Century’” was minted in 1988 in a joint communiqué issued by India’s prime minister Rajiv Gandhi and the Chinese chairman Deng Xiao Ping at the end of a Sino-Indian summit meeting meant to reconcile the two countries after decades of antipathy and one border war. Twenty-two years later the term has outlived its creators and no longer seems like the hyperbole it was then, but rather a simple statement of fact. For those who believe in globalisation, China has assumed something of the same status cargo cults had for some south west Pacific islanders. And if your principal source of news is the business media, you will be hard pressed not to believe in the Indian miracle. Why shouldn’t you? It is not just the professional pitchmen of CNBC or Bloomberg news who routinely make these claims. Leading figures in the business world – from Goldman Sachs’s embattled chairman, Lloyd Blankfein, who has said he views India as one of world’s most promising markets, to the very un-embattled Michael Moritz of Sequoia Capital (the Silicon Valley investment firm that took Google public) – are equally convinced that the 21st century will have India at its centre. Whether this turns out to be one more case of the popular delusions of crowds, in the manner of Holland’s 17th-century tulip mania or the South Sea Bubble in 18th-century England, or instead is borne out, is anything but clear. But it is beyond doubt that the triumphant idea of India’s inexorable rise stems as much from a clever PR campaign by the Indian government and business establishment (to the extent that they differ at all) as from a cold calculation of growth rates and market share, impressive though these unquestionably are. Indeed, the only previous example of such a successful national “re-branding” was that undertaken by New Labour in the aftermath of Tony Blair’s victory in 1997 – Cool Britannia, the so-called Millennium Products’ initiative, and the rest. But that already had been prefigured by reports by the Design Council – A New Brand for a New Britain, and Demos – Britain: Renewing our Identity, which further blurred the lines between nationalism and commodification. For India, the first effort at such rebranding had been mainly directed at a domestic rather than an international audience. It came in the form of “India Shining”, which started as a pitch to attract tourists but almost immediately was picked up as the campaign slogan for the then ruling Hindu nationalist BJP party in the run-up to the 2004 general election. In it, pride too became commodified. As the campaign’s designer, Prathap Suthan, creative director of the Indian branch of the New York-based Grey Worldwide advertising agency, put it at the time, “India Shining is all about pride. It gives us brown-skinned Indians a huge sense of achievement. Look at the middle-class and they tell the story of a resurgent India.”… To read the rest of the article please subscribe to the Frontline Broadsheet. Its only £15 per year for four issues.  The shining face of success that the country presents to the world disguises deep tensions between great wealth and extreme poverty. With the commonwealth games approaching, David Rieff looks at the politics that sustains such divisions and wonders whether the dream of the Asian century still has meaning for this divided culture.

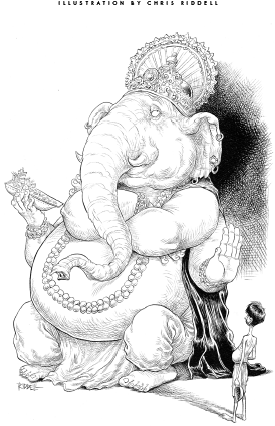

The shining face of success that the country presents to the world disguises deep tensions between great wealth and extreme poverty. With the commonwealth games approaching, David Rieff looks at the politics that sustains such divisions and wonders whether the dream of the Asian century still has meaning for this divided culture.