Guest Post: Votes we can believe in (Felix Kuehn)

It’s the middle of summer down here in Kandahar, with temperatures peeking around 50 degree celsius by noon. In the run up to Afghanistan’s second presidential and provincial council elections foreign troops stepped up their efforts, launching multiple operations to prepare the ground for voters.

British casualties passed the 200 mark, with friends from London writing to me asking what is happening down south. There is a growing belief that a surge and COIN is the answer, and that pouring more troops in now will allow them to withdraw sooner in the long-term. Some commentators even suggested that this could happen in the next one to two years — an unlikely scenario to say the least.

These elections are a milestone in the western ‘Afghanistan’ project. There’s a definite need for this to happen; there’s a definite need for good news. The south is in the midst of an ever accelerating downward spiral of violence and disintegration: take last year’s numbers of casualties, attacks and bombs, as well as foreign troops; double it and you are close to what Kandahar is like these days.

The city itself is in deep crisis. Just the other day a friend named multiple city districts he can not go to anymore due to security concerns. If you are known in the city, you carry a gun.

The Afghan government has sent in reinforcements to secure the city. On my flight from Kabul last week I shared the plane with some 40 ANP. New soldiers and policemen in Kandahar means scared kids with guns, which in turn translates into more gun fights and more problems. During the two nights before the election the air was filled with spurts of AK and PK gunfire, at times lasting for over an hour, maybe because the insurgents are stepping up or because the police are edgy and trigger happy.

The day before the elections Alex forced me onto twitter and posted an introduction resulting in 40+ followers, one of which send me a tweet at 7.30am saying: “@felixkuehn Wake up. It’s a big day.” Indeed it was, and by the time I was back from the first round of visits to various election polling stations I saw his message.

The stations opened at 7am, with the governor casting the first vote of the day just a couple of minutes before the elections officially started. It’s a two minute drive from where I live to the election centre at Ahmed Shah Baba High School; at least it only takes 2 minutes on election day. All the roads were deserted, the city closed. Cars needed special permits to be on the street, shops were closed and there were double the usual number of ANA and ANP-manned security checkpoints throughout the city.

I took a picture of the governor. He didn’t look happy walking to the station; he hardly ever looks happy you have to admit, but than again, who would be happy running Kandahar…

He cast his vote at one of the 20 polling rooms amidst a battle among the who is who of Kandahari journalists. NYT’s Timur Shah, Hewaad television and Al Jazeera were swarming around him, and of course Soraya Nelson of NPR, just back from two weeks embedded in Helmand, was holding her ground, moving ninja-like through the crowd in her orange garments. When we entered the school grounds about quarter to seven, flashing our media cards from the election monitoring commission, we were greeted by a few friends, the election ‘observers’, all wearing Karzai caps and buttons.

We stuck around at Ahmad Shah Baba for an hour or so. At no point during that time did more people come to vote other than election staff and journalists hanging around waiting for them.

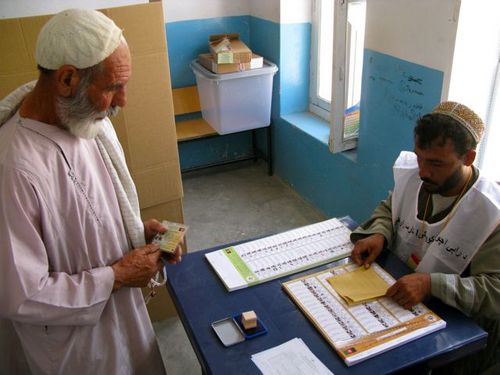

The caravan of journalists then poured into their cars heading for the next polling station — which was closed, so we drove to the next one. Zahir Shahi High School is a few hundred meters down the street from the police headquarters and had 8 polling stations open. When we arrived there was a small queue of around 8-10 people outside, but inside the corridors were full, giving an impression that lots of people would show up to cast their votes here. In the end the total number that came was around 1800 (1717 votes at 3.15pm with hardly anyone around); this being Kandahar’s most central polling station, a very meager outcome.

At Zahir Shah High School, however, we met Mr. Zakaria who was there to cast his vote. “I am not afraid. I am here to vote,” or something pretty close to that were his words. After his finger was stained and his card invalidated, he took the two voting cards and walked towards the cardboard voting stations with one in each hand. 30 seconds later he appeared again a voting paper in each hand, shrugging his shoulders, and asking the room what he actually had to do with them now. Several people rushed to help and a minute later, Mr. Zakaria disappeared again. Another man went over while he was standing behind the cardboard shield but was soon asked by the staff to stand back. Mr. Zakaria dropped the ballots into the boxes and and strolled away.

We walked around the corner to go the the women’s polling station. There were a few dozen there at the time, even though half of them were probably election staff. We went into one of the polling station rooms, and found ourselves in the middle of a drama: the ballot boxes weren’t sealed before the voting had started.

In the end, one of the ladies in the room sealed the boxes and stuffed the 14 ballots into them again, and we were sent on our way.

We spent lunch at our computers, quickly learning that the supposedly indelible ink could be removed with bleach. The news was tearing through Kandahar by 1pm. Everyone was on the phone, letting people know that you could remove the ink and vote again. Close to everyone I know down here has 2-3 voter registration cards to his name. I can not be sure how many people cast a second or even third vote, but I know it happened.

After lunch we drove out to Mirwais Mina just west of Kandahar city. Mirwais Mina sees open fighting on the street as well as IED attacks on a regular basis these days. The school we went to, however, is best known for the acid attacks against a number of schoolgirls earlier this year.

In the polling station for men we were escorted to one of the offices as soon as we entered the compound. Ustaz Abdul Halim was sitting in the middle of the room, smoking. Ustaz is the last of the Kandahari dinosaurs of the Soviet Jihad, and Mirwais Mina is his capital. He still has a base out there, and remains pretty influential to say the least. He was the security advisor to the last governor, and a few days ago I saw him on the stage of Karzai’s rally in the stadium. Ustaz seemed to be in high spirits, though, and after a brief chat we walked up the alley to the girls’ school.

At that polling center 94 women had cast their votes at 3.05pm.

With barely an hour left we drove to Shkarpur Darwaza Station, counting 274 votes, and hurried back to Ahmad Shah Baba High School where the day had started. We went to 16 out of the 20 stations at Ahmad Shah Baba, counting 1007 votes, while rockets hit a few hundred meters away from the school causing the ANP and ANA to hastily run towards the gate and number of people to move towards the back of the compound.

We stuck around, watching them seal the ballot boxes and then open them again under supervision, counting the

votes. A journalist came in saying that the BBC had announced that the stations would be open for an hour longer, but people were already counting.

There are about 60 polling stations in Kandahar city and about 260 in the entire province. If I average what I saw on election day (and remember that two of those were the biggest in Kandahar province), and I use only the male polling stations, the most accessible etc. then I arrive at a participation rate of roughly 170,000 people or 17% for the whole province.

But, let’s be real: this is Kandahar. In the 2005 Wolesi Jirga elections roughly a quarter of all registered voters were female. I can’t recall the exact percentage but that number has grown in this year’s registrations, a miracle in itself down here in Afghanistan’s conservative heartland. So at least a quarter of the polling stations are for female voters, leaving 195 male voting stations. Let’s see where that leaves us – at roughly 13%.

In Kandahar we have 1.08 million registered voters. Out of those votes cast in the city we have a number of people who voted twice or maybe three times. In Spin Boldak, General Raziq took all the ballot boxes into his house, and rumour has it that the outcome for the presidential election in Boldak is 100% in favour of Karzai. People are talking about a 60% turnout by now. Based on what I saw and heard, a realistic estimate for the province is somewhere between 6-8%. As I told a friend who might be in the election complaints commission, and therefore a very busy man soon: “down here in Kandahar there was no election.”

But who are we kidding? It’s a milestone achievement. And in the end we will learn that at least 50-60% of the people voted, some 500,000 to 600,000 people. This was the second independent, free, fair and democratic elections in Afghanistan.

Karzai and Abdullah have both already declared their victory.

These elections were at best a sham, but in reality it was pure satire – no wait – actually it’s a divine comedy, and the foreigners are really just visiting the seven circles of hell.

[This post is by Felix Kuehn, my colleague down in Kandahar. It was originally posted over on his blog at www.felixkuehn.com.]