Georgi Vanyan: Every family has the desire for peace

Fifteen years after the 1994 ceasefire put the conflict over the disputed territory of Nagorno Karabakh on hold, reports that the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan might be moving closer to a final peace settlement have caught many unaware. The last time international mediators were as optimistic about the prospects for peace was in 2001 at Key West, Florida. However, no agreement materialized. This time round, many observers and regional analysts hope the situation will be different.

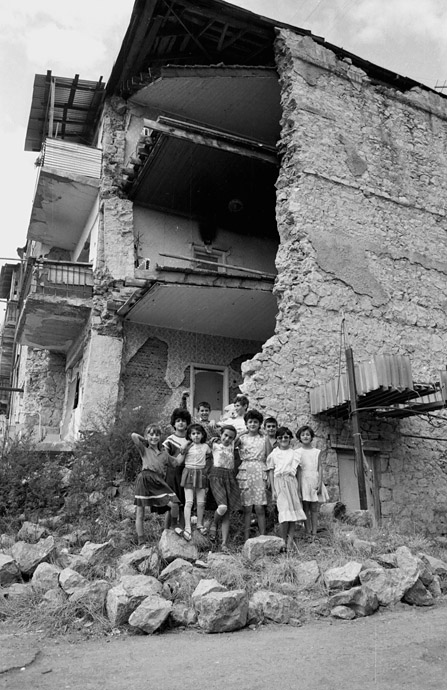

War in the early 1990s claimed around 30,000 lives and a million refugees and IDPs were forced to flee their homes. Armenian forces currently control around 16 percent of Azerbaijan, including Nagorno Karabakh itself, but skirmishes still regularly break out on the frontline. Indeed, with its newly found oil wealth translating into massive military spending, some analysts fear that Azerbaijan might wage a new and more devastating war if a peace deal is not signed in the near future.

Emotions run high in both countries, but given the ability of Azerbaijan’s president, Ilham Aliyev, to silence and suppress any dissent, the situation is of more concern in Armenia. Nationalist political groups are not only more established, but might well be joined by a newly-formed opposition coalition still reeling after it was brutally crushed following last year’s disputed presidential election. At the very least they hope that exploiting inherent fears about a peace deal will bring down the government.

In fact, argue many analysts, the Nagorno Karabakh conflict has defined local politics in Armenia and Azerbaijan since even before independence from the former Soviet Union was declared in 1991.

Civil society has gotten in the act too, with many of those actually involved in various conflict resolution initiatives opposing a deal. Others, such as former actor and theatrical director Georgi Vanyan, argue that peace is necessary for Armenians and Azerbaijanis alike. Arguably one of the few genuine activists in this area in Armenia, Vanyan spoke to the Frontline Club this week at a café in central Yerevan just as media in both countries reported on his plans to stage an Azerbaijani film festival in the capital this autumn.

Already no stranger to controversy, Vanyan has often been branded a traitor by nationalists, and not least since his last initiative, Days of Azerbaijan, was staged at a public school in Yerevan towards the end of 2007. The event was briefly disrupted by a small group of nationalist bloggers opposed to any concessions to Azerbaijan. And when former President, Robert Kocharian, declared that Armenians and Azeris were “ethnically incompatible,” Vanyan staged a joint jazz concert by musicians from both countries to prove him wrong.

For some in Armenia, however, Vanyan’s approach is considered almost "treasonous." The 46-year-old activist answered such criticism in an interview published by an Azerbaijani newspaper last week. “Communication is not betrayal,” Vanyan was quoted as saying. “It is a natural human need.”

Azerbaijani Prisoner of War, Stepanakert, Nagorno Karabakh © Onnik Krikorian / Oneworld Multimedia 1994

Such communication, however, is sadly lacking and what conflict-resolution initiatives do exist are often held behind closed doors with access to the media tightly controlled or even prohibited. Vanyan says that such an approach is highly flawed. “The approach of keeping everything closed carries with it some very grave consequences,” he says, adding that instead of presenting a paper at a conference on the conflict he instead decided to ask participants if they actually wanted to resolve the issue.

“Many individuals involved in these peace-making initiatives don’t have any interest in seeing the conflict resolved because they have a certain ‘visibility’ and also financially gain from the situation,” he explains. “Churchill said that in order for corruption to flourish there is the need for an external aggressor. Everything is calculated, including the nationalist rhetoric injected into society. The mass media is part of this too. “

This situation, Vanyan argues, suits both the government and opposition who at various times have exploited Karabakh for short-term political gain. Indeed, Armenia’s first president, Levon Ter-Petrossian, was forced to resign in 1998 by hardliners in his own government after he advocated a compromise peace deal and penned an article “War or Peace?” In that opinion piece, Ter-Petrossian wrote that he believed Armenia hadn’t won the war with Azerbaijan, but only a battle.

Proposals which envisaged the return of territories under Armenian control surrounding Karabakh, but which indefinitely delayed any decision on the territory’s status, gave rise to suspicions that Ter-Petrossian was ready to accept its autonomy within Azerbaijan and led to his downfall. Now leader of the extra-parliamentary opposition in the country, Ter-Petrossian hopes that history will be repeated and Karabakh can again be used to return to power.

|

“None of the dominant political parties have any programs or policies and have to fill this vacuum of empty rhetoric with something,” says Vanyan. “Indeed, if you compare what Levon Ter-Petrossian was saying ten years ago with what he is saying today his rhetoric indicates that he is striving for power. Ter-Petrossian had all the preconditions to achieve peace, but he closed the way with his article. Now, all the political parties accuse each other of being ready to ‘sell out’ Karabakh.”

“The phrasing of the question, “War or Peace?,” is criminal because everyone wants peace and such an alternative should not be offered. I do not accept this approach.”

Vanyan is also critical of the lack of any concrete policy from successive presidents and governments in Armenia. “Azerbaijan has a policy. The war has been de facto stopped and it is developing its economy instead while also recreating regional communication networks,” he says. “Ilham Al

iyev continues the same policy while also trying to convince the international community that Armenia is the aggressor and occupies Azerbaijani territory. However, everything else is leading in the direction of war. “

Instead, Vanyan argues, there needs to be new approaches taken to prepare society for peace. Indeed, he says, the desire to end the conflict needs to be there in the first place. “Armenians and Azerbaijanis are human beings first of all and have a basic desire for peace. What we need to do is to make this basic desire public and to initiate some kind of open public discussion. Instead of organizing seminars and talking to NGOs, we talk to people in the markets, or in local cultural centers.”

However, admits Vanyan, there are many obstacles to overcome. In 2007, when two journalists from Azerbaijan were invited to conduct master classes for pupils at a Yerevan school, there was resistance from some teachers and parents. “They argued that Armenia is still in a state of war and such initiatives threatened its existence,” he says. “However, such a mentality is actually suicide, and even if society might seem very intolerant, each and every family has the desire for peace.

Meanwhile, I don’t consider the peace talks as such because both sides speak with the language of war. And while I’m grateful to the international community for attempts to resolve the conflict, it could also lead to later resentment. It’s why we hope events such as our Azerbaijani film festival will start some kind of discussion in Armenian society.”

Top and second from bottom photos: Stepanakert, Nagorno Karabakh © Onnik Krikorian / Oneworld Multimedia 1994. Bottom photo: Armenian refugee, Yerevan, Republic of Armenia © Onnik Krikorian / Oneworld Multimedia 1994