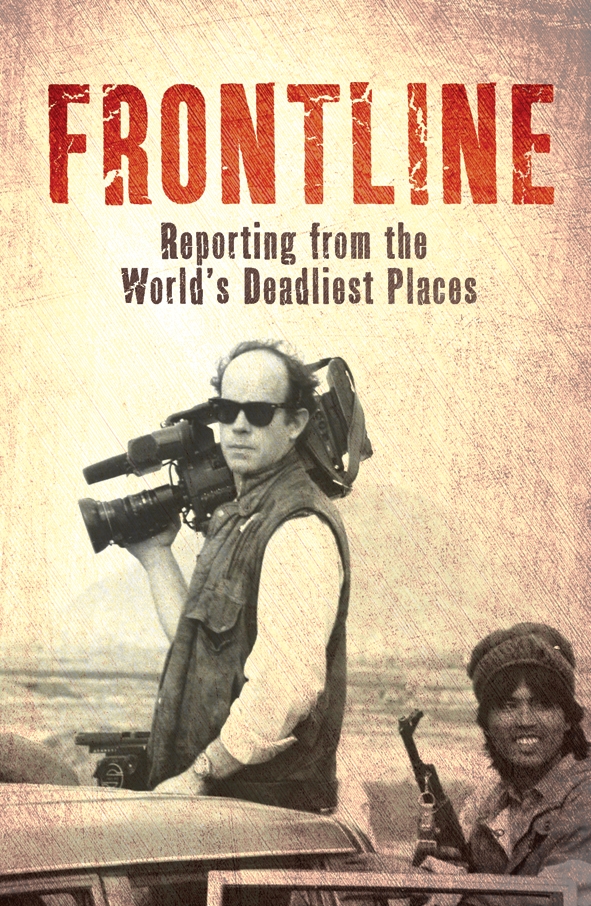

Frontline: Vaughan Smith Shot in Kosovo (1998)

Earlier this week we posted the first of two excerpts from the newly revised and updated edition of Frontline by David Loyn, published last month by Summersdale.

The acclaimed book tells the gripping story of the Frontline news agency, founded by journalists Rory Peck, Peter Jouvenal, Vaughan Smith and Nicholas Della Casa.

The second excerpt, a compelling account of Frontline Club founder Vaughan Smith being shot by a sniper in Kosovo, can be found below…

*****

Pristina, Kosovo, March 1998

The pain did not feel like anything to worry about, just a little discom fort at his waist. It must have been a stone kicked up by one of the thirty rounds from an AK47 that had been fi red directly at him as he ran along a low ditch, crouching to try to escape detection. Or perhaps it was a ricochet at worst, a spent bullet which had bounced up at him from somewhere.

fort at his waist. It must have been a stone kicked up by one of the thirty rounds from an AK47 that had been fi red directly at him as he ran along a low ditch, crouching to try to escape detection. Or perhaps it was a ricochet at worst, a spent bullet which had bounced up at him from somewhere.

It was the least of Vaughan’s problems as he lay flat on the ground wondering how to get out alive. Damn the farmer who had led them out this way! When they had come in earlier Vaughan had had some control over the operation, taking time to crawl unnoticed through the curious knee-high oak trees that carpeted the Kosovar hills. The farmer guiding them had pointed out the direction they needed to go, and then Vaughan had led them slowly, evading the cordon the Serbian police had put around the area. It was not a particularly effi cient cordon, and the men who were spread out in the woods were very visible in their blue uniforms. But it was a cordon nonetheless, and its aim was to stop anyone interfering with whatever the Serbs were doing on the other side of the hills.

Vaughan knew where he would mount a cordon, if he had been the Serbian commanding officer, and he had outguessed the Serbs to make his way slowly towards the columns of smoke that rose beyond the hills. But once he had finished filming, the farmer had headed off on a different and more direct route out. He had gone too far before Vaughan could signal to him to stop without drawing attention to himself. There was nothing for it but to follow him. And now they had been seen and shot at. Next to him, lying on the ground, was Kenny Brown, a gentle, humane and very competent Glaswegian, who had recently joined Frontline. When they waved at their guide, he slowly crawled back to them, and they successfully retraced their steps to make it out safely, running fast across the only stretch of open ground.

It was not until they arrived back at their car, some five miles away, that Vaughan realised he had been shot. He took out his mobile phone to call his wife and discovered that it was just a pile of broken metal, with the remains of a bullet embedded in the battery. The shot, a .762 round from a modified sniper version of an AK47, had been slowed down by a wad of Deutschmarks – the money now had a hole neatly drilled through the middle. The phone and money had been wrapped up tightly in a green handkerchief in a bumbag strapped around Vaughan’s waist. If he had not been carrying it, the bullet would have gone straight into his side. He lifted up his shirt and realised that he had a large bruise on his stomach, but nothing worse.

At least the risk had been worth it. The pictures he had taken were the first significant shots fired in a new Balkan war. They showed systematic destruction as men threw bottles full of petrol into houses to set them alight: the first real evidence that the Serbs had begun a major campaign in Kosovo. There were to be three big landmarks in the ratchet towards NATO bombing over the next year; this was the first of them. During the long months of the war which lay ahead no other cameraman would get as close as Vaughan had to Serb armoured vehicles in the act of knocking down houses. When the Dutch army saw the film they recognised the armoured vehicles as those that had been taken from them by the Serbian butchers at Srebrenica, the worst massacre in the Bosnian war. This evidence was a direct forensic link between the two conflicts. Despite being shot getting the pictures Vaughan was not named in the BBC report that used them that night; he was just another freelance cameraman.

*****

Frontline: Reporting from the World’s Deadliest Places can be purchased by visiting this link.

Reproduced by kind permission of David Loyn and Summersdale Publishers.